After a serendipitous encounter at Austin Community College, I asked Bill Whisenant, author of Psychological Kinesiology: Changing the Body's Beliefs to come into the studio for a chat. I heard his presentation on "Enhancing Creativity", and wanted to share his messages about tapping into the creative recesses of the brain with the members at Violin Lab. Coincidentally, Bill had just taken up viola and recognized me from from his online quest for instructional videos on viola playing.

During this interview, a scary thing happened. Bill asked me to improvise on a simple chord progression. As a classically trained musician who is rarely divorced from the "page", I find improvisation to be stressful. My expectations for quality performance over-ride any enjoyment I might possibly derive. Years of training for polished performances do not leave a great deal of room to "mess around". But it is precisely in the "messing around" that, according to Bill, unleashes creativity in other aspects of our lives, even in unexpected ways. So, that being said, I humble myself before anyone who watches this next part of the interview.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Saturday, July 24, 2010

Violin Practice Fundamentals, part 5: Wood shedding

Let the Wood Shedding Begin

It wasn’t until I was well into my first year of college when the weekly assignments of scales, etudes, sonatas…grew to what seemed like unmanageable amounts. There weren’t enough hours in the day to practice everything. One of the most important skills I learned was how to woodshed. The concept was pretty simple: practice a very small chunk of music over and over until you get it right. In a word: repetition. It wasn’t until graduate school however, that I realized mere repetition was just not sufficient to exact the kind of progress I wanted to see happen. I had to refine the good old-fashioned wood shedding technique by infusing it with heightened awareness and mindfulness.

It wasn’t until I was well into my first year of college when the weekly assignments of scales, etudes, sonatas…grew to what seemed like unmanageable amounts. There weren’t enough hours in the day to practice everything. One of the most important skills I learned was how to woodshed. The concept was pretty simple: practice a very small chunk of music over and over until you get it right. In a word: repetition. It wasn’t until graduate school however, that I realized mere repetition was just not sufficient to exact the kind of progress I wanted to see happen. I had to refine the good old-fashioned wood shedding technique by infusing it with heightened awareness and mindfulness.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

Violin Practice Fundamentals, part 4: Mental Bookmarking

Practicing in many ways is an opportunity for self-care. As our own compassionate audience member, we are forgiving, yet exacting. Non-judgmental, yet objectively critical. In this next stage of practice, we pull back from the hyper-focused roll of team coach and take a seat on the bleachers. As we watch the game we assess the bigger picture. What is the overall score and where do we need to concentrate our efforts? Now we assess the weaker links of the team to be later subjected to the rigors of wood-shedding.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Violin Practice Fundamentals, part 3: Thoughtful Anticipation

It's still not time to speed it up yet! The previous step was the input process, where we fired thoughts in succession, giving our arms and fingers necessary information to "know" what to do. However, knowing what to do and being able to do it are two different things. Now we start honing the ability to think ahead. This is the stage I refer to as "thoughtful anticipation" where we are able to think the next action before we get there and can prepare our technique to refine execution.

Violin Practice Fundamentals, part 2: How Slow Can You Go?

Everyone knows that slow practice is critical to learning difficult passages in a piece of music. The problem is that slow practice becomes tedious and boring very quickly, so we perfunctorily slow down for a spell then move on. But before long, we find that we're not improving at the rate we would like to, so we revisit the notion of "slowing down".

For the violinist, any passage of music usually involves a myriad techniques occurring at the same time, and there is no way to pay attention to everything at once.

For me, slowing a difficult spot down to crawling tempi allows ample time for mentation and execution.

I call the the first step of slow practice the "identification" step, where we give ourselves the time to input each tiny piece of data required to play a particular passage well.

Techniques:

String Crossings

Interval Relationships

Intonation

Bow Distribution

Articulation

etc.....

For the violinist, any passage of music usually involves a myriad techniques occurring at the same time, and there is no way to pay attention to everything at once.

For me, slowing a difficult spot down to crawling tempi allows ample time for mentation and execution.

I call the the first step of slow practice the "identification" step, where we give ourselves the time to input each tiny piece of data required to play a particular passage well.

Techniques:

String Crossings

Interval Relationships

Intonation

Bow Distribution

Articulation

etc.....

Sunday, July 4, 2010

Violin Practice Fundamentals, part 1: Find Your Comfort Quotient Number

Prologue:

It has taken a good many years for me to hone good practice techniques, and even still I have much to learn. My earliest memories of practicing were “playing through” my Suzuki songs, one by one, with my mom accompanying me on the piano. My childhood practice methods didn’t extend to any degree of critical listening or reflection, much less thoughtful repetition.

My great “AHA” moment came when I was in middle school. It was the day before our studio recital and I had the stark realization that I couldn’t play through my recital piece without stumbles and hesitations. It was then, out of sheer desperation, that I finally did what I’m sure my teacher had been professing for years: I practiced. I actually remember dividing the piece into sections repeating each one many times until I got it right. EUREKA! It worked! My teacher said the next day after the recital, “I’m surprised you played it that well. You must have really practiced.” I assumed she meant I must have practiced hours and hours. In reality it was a relatively short session, (about an hour and a half, maybe), just a very focused one! Now had that experience truly become the pivotal moment where all the tried and true methods of efficient practice had become an institution of daily life, I would be a far better player than I am now. Sadly, it took a good many more years to rehabilitate old, ineffective habits.

Fast -forward about 30 years. As a teacher I’ve come to realize the importance of guiding a student through the practice process. I frequently "practice" with them in the lesson. We call those days " boot camp". It's kind of like the old adage: Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime. The following blog entries cover what I feel to be the basic principles of good practice habits.

Part 1: Ratings System: the Comfort Quotient Number

You’ve found a piece you would like to play. It’s a little beyond your present abilities. You could start at the beginning working your way through the snags as they appear. But as an intelligent person you already know it’s more efficient to find the biggest tangles first and proportion much of your time on them. The problem is that there usually are many tricky places. In the following videos I share my little system to determine those places of highest priority.

Step 1: Find Your CQ 10

Step 2: Ranking for Highest Priority

Thursday, June 10, 2010

Frustration and Practicing the Violin

As far as taking on a new instrument goes, violin is no walk in the park. The complexity of its sound is equally matched by the complexity of learning to play it. Those of us who have dedicated hours and years of our life working to pull beauty from of a piece of wood, know that playing the violin can be synonymous with frustration, which, is a frequent topic for discussion as well as commiseration at Violin Lab.

The belief that adult beginning violinists have a harder time learning violin than kids, in my opinion, is untrue. The learning curve is steep for any age group. The majority of children (there are those amazing exceptions, of course) learn violin at a very slow pace. It takes many years for most kids to reach a level of competency and a good many years after that to become seasoned players. It has taken my oldest daughter 7 years to reach the end of Suzuki book 4, and if I could bottle up all the tears she shed and frustration she felt over those years I could have something potent to sell to the military.

For kids, frustration is the enemy. It is why my youngest daughter, refused to go to her piano lesson the other day, because the night before she kept stumbling at the same place in one of her piano pieces and couldn’t work through it in time for her lesson. A good friend’s daughter quit the violin after years of lessons because, and I quote, “it was too much of a struggle”.

Most kids (yes, most) eventually stop playing. Other extra-curricular activities and heavier homework demands in high school account for a hefty percentage of the attrition. But how many quit because “it isn’t fun”, or as my daughter has said many times, “it’s boring”? It’s my guess that the biggest difference between them and us, is that we embrace new and challenging. My gym instructor shouted with great enthusiasm this morning, “It’s fun to struggle” as she had us rolling a large ball back and forth with one leg while doing lunges with the other leg. It was true. It was fun, and in my ripe middle age I find the more I have to apply myself to something, the more thrilling it is to do. And the greater the challenge it is, the more gratifying the accomplishment. For me, boring is staying in my comfort zone, doing what I already know how to do. (e.g. I’ve never blogged before now)

Einstein’s definition of insanity was trying the same thing over and over expecting different results. If that’s true then surely all kids are insane. I watch my own children and young students stumble at the same measures, backtracking to make another perfunctory pass, stumble again, never really fixing the problem with thought and patience. This of course breeds frustration, and once a kid reaches that point, they either go on to something else or stop practicing altogether. Kids are incredibly imaginative beings, but not at practicing. And that’s where we adults excel. We have at our disposal years of imaginative problem solving tools. We continually work out relationship issues with friends, family and colleagues. We have skills sets that can magically “make things happen”: we throw odds and ends together to make a dinner, a school project, or a Halloween costume. Kids have the advantage of rapidly developing synapses, but we know how to access the complex synaptic pathways that have been webbing over decades to create a resourceful and impressive toolbox.

After a lifetime of playing the violin, frustration has an entirely different meaning for me than it did in my youth. Now it is the motivational trigger to figure out why something is not working. When I have one of those days when everything sounds slightly out of tune and scratchy, even when the day before it felt “like butter”, I utter a few choice words, then, I turn my game on. At that point I have a mission and it is my job to figure out the missing piece of the mental puzzle. Although I would prefer to play perfectly, never missing a single note, I am honestly intrigued by the challenge of discovery. I continually have the thought that there is some buried mental construct I have yet to unearth. I love the charge I get when a new notion passes through my brain, a perfect analogy or mental picture that sheds light on the connection between mind and body. Now that never happened when I was a kid.

Frustration is evolutions way of keeping us from a life of complacency, to keep searching for better ways and solutions. If “Necessity is the Mother of Invention”, then frustration is the nagging sister. Would we be vacationing in the Cayman Islands if Orville and Wilbur hadn’t felt “frustrated” at the limitations of their man operated gliders?

So although I’m not the least bit pleased with my presbyopia, stiff neck, or short term memory challenges, I am happy that the maturation process is making me more clever and inventive in the areas of my life that are meaningful.

And for those less meaningful times in life, well, frustration has a way of knocking me down. Really, how many more times in my life do I need to bang my toe into a chair leg, miss my exit off the highway because I was “lost in thought”, or burn yet another unattended pot on the stove? And why does the intense frustration I feel each time not motivate me to “search and discover” some new remedial system to make things better? I would love for someone to blog about that.

--Beth Blackerby

creator of www.ViolinLab.com

The belief that adult beginning violinists have a harder time learning violin than kids, in my opinion, is untrue. The learning curve is steep for any age group. The majority of children (there are those amazing exceptions, of course) learn violin at a very slow pace. It takes many years for most kids to reach a level of competency and a good many years after that to become seasoned players. It has taken my oldest daughter 7 years to reach the end of Suzuki book 4, and if I could bottle up all the tears she shed and frustration she felt over those years I could have something potent to sell to the military.

For kids, frustration is the enemy. It is why my youngest daughter, refused to go to her piano lesson the other day, because the night before she kept stumbling at the same place in one of her piano pieces and couldn’t work through it in time for her lesson. A good friend’s daughter quit the violin after years of lessons because, and I quote, “it was too much of a struggle”.

Most kids (yes, most) eventually stop playing. Other extra-curricular activities and heavier homework demands in high school account for a hefty percentage of the attrition. But how many quit because “it isn’t fun”, or as my daughter has said many times, “it’s boring”? It’s my guess that the biggest difference between them and us, is that we embrace new and challenging. My gym instructor shouted with great enthusiasm this morning, “It’s fun to struggle” as she had us rolling a large ball back and forth with one leg while doing lunges with the other leg. It was true. It was fun, and in my ripe middle age I find the more I have to apply myself to something, the more thrilling it is to do. And the greater the challenge it is, the more gratifying the accomplishment. For me, boring is staying in my comfort zone, doing what I already know how to do. (e.g. I’ve never blogged before now)

Einstein’s definition of insanity was trying the same thing over and over expecting different results. If that’s true then surely all kids are insane. I watch my own children and young students stumble at the same measures, backtracking to make another perfunctory pass, stumble again, never really fixing the problem with thought and patience. This of course breeds frustration, and once a kid reaches that point, they either go on to something else or stop practicing altogether. Kids are incredibly imaginative beings, but not at practicing. And that’s where we adults excel. We have at our disposal years of imaginative problem solving tools. We continually work out relationship issues with friends, family and colleagues. We have skills sets that can magically “make things happen”: we throw odds and ends together to make a dinner, a school project, or a Halloween costume. Kids have the advantage of rapidly developing synapses, but we know how to access the complex synaptic pathways that have been webbing over decades to create a resourceful and impressive toolbox.

After a lifetime of playing the violin, frustration has an entirely different meaning for me than it did in my youth. Now it is the motivational trigger to figure out why something is not working. When I have one of those days when everything sounds slightly out of tune and scratchy, even when the day before it felt “like butter”, I utter a few choice words, then, I turn my game on. At that point I have a mission and it is my job to figure out the missing piece of the mental puzzle. Although I would prefer to play perfectly, never missing a single note, I am honestly intrigued by the challenge of discovery. I continually have the thought that there is some buried mental construct I have yet to unearth. I love the charge I get when a new notion passes through my brain, a perfect analogy or mental picture that sheds light on the connection between mind and body. Now that never happened when I was a kid.

Frustration is evolutions way of keeping us from a life of complacency, to keep searching for better ways and solutions. If “Necessity is the Mother of Invention”, then frustration is the nagging sister. Would we be vacationing in the Cayman Islands if Orville and Wilbur hadn’t felt “frustrated” at the limitations of their man operated gliders?

So although I’m not the least bit pleased with my presbyopia, stiff neck, or short term memory challenges, I am happy that the maturation process is making me more clever and inventive in the areas of my life that are meaningful.

And for those less meaningful times in life, well, frustration has a way of knocking me down. Really, how many more times in my life do I need to bang my toe into a chair leg, miss my exit off the highway because I was “lost in thought”, or burn yet another unattended pot on the stove? And why does the intense frustration I feel each time not motivate me to “search and discover” some new remedial system to make things better? I would love for someone to blog about that.

--Beth Blackerby

creator of www.ViolinLab.com

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

My Interview by Ralph

Meet Ralph, one of my hip online marketing consultants, who teaches us that it's ok to wear large, bold horn-rimmed glasses if you're intelligent, funny, and under 40 living in a quirky metropolis like Austin, TX. Anyway, he and OJ my other hip consultant, who doesn't wear bulky glasses but could because he's that cool, thought it would be fun to interview me, to offer readers a refreshing departure from my usual solitary authoritative position in front of the camera.

I had a lot of fun and the whole event gave me insight into the fact that a) I seriously like to talk and b) I enjoy telling others who I think may not know anything about playing the violin and how it works.

Thursday, May 27, 2010

Brains, Adults, and Violins

All the latest research shows that middle-aged brains are better suited and more "talented" for tackling complex tasks than younger brains. This is great news if, like me, you are pushing 50 and have a long "things to do before I die" list. I originally posted this clip on Violin Lab but wanted to share it here too. I interviewed Glen Leupnitz, a brilliant scientist who is actively involved in anti-aging research. He has multiple PHDs, developed the canine parvo vaccine and was named by the International Biographical Centre, Cambridge, England, as one of "2000 Outstanding Intellectuals of the 20th Century" for outstanding contributions to the field of medicine. I thought it would be great to hear straight from the horse's mouth why learning violin as an adult is an excellent way to combat aging. I also asked, on my own behalf, if after 41 years of playing it was still possible to improve, to "up my game" so to speak.

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

Is it Too Late for Adults to Learn to Play the Violin?

As I have created an entire website designed to teach adult beginning to intermediate violinists, you can guess that my response to the title question of this blog is a resounding “NEVER”. It is certainly in my business interests to be a strong advocate for adults learning to play the violin.

But that's the chicken. Here is the egg. Approximately 17 years ago, before there was ever a Violin Lab, I started an adult chamber music class at Austin Community College. I already had a booming private studio of young talented kids, and one beginning adult student, a thirty-something year old, who had played some brass instrument in junior high band, but passionately wanted to learn the violin. Leslie was her name and she was my first adult student.

She came to lessons knowing how to read music, but that was about it. She experienced a lot of anxiety in lessons, her nerves manifesting obvious tremors in each bow stroke. After our first couple of lessons, I thought for sure she wouldn't last. I saw the long, arduous battle in front of her, and many times, I must admit, I thought of suggesting that she choose another instrument, something easier, like piano or guitar. What I absolutely couldn't see then was the depth of her resolve, nor could I have anticipated what she would accomplish over the next several years, reaching a level of proficiency rivaling that of a much younger student. Although she was still subject to nervous anxiety, (it frustrated her to no end) she never let it stop her. She eventually tackled the Mozart G major Concerto, Kreutzer Etudes, and a few Handel and Corelli sonatas. As I watched Leslie develop into a competent violinist, my own ideas and feelings changed about teaching adult students. Perhaps I had bought into what our goal-oriented society tells us: that unless we can “master” or “monetize” something, then why bother doing it? And certainly, given the extreme difficulty of learning the violin, if you missed the boat when you were young, then you were better off doing something easier. We are rarely encouraged to dedicate ourselves to a goal simply to develop our artistic selves, nurture our souls, or expand our ways of thinking, detached from any outcome.

Teaching Leslie opened my mind to the idea that learning to play the violin was about self-discovery through process and opened my heart to feelings of outright jealousy.

Throughout my then 25 years of playing the violin, I had enjoyed many technical milestones and accomplishments. I had experienced the utter poetry of pulling deep resonating tones from ancient wood with a stick that felt like a feather beneath my fingertips. I had performed pieces where in pure sweet moments of transcendence I had merged so deeply with the melody that I lost my sense of self. But because I started as a child I had never experienced what my adult student had: the burning desire to learn the violin; the self-propelling passion that comes from choice, the will to continue because it was what I wanted more than anything. Those things I had never owned. For me learning to play was the byproduct of a childhood activity chosen and nurtured for me by my mother, like an arranged marriage, and later the byproduct of a vocational decision to the dilemma faced by every young adult: “What am I going to be when I grow up?”

After a few years of lessons, Leslie’s skills were sharpening and I thought it would be nice for her to play with other people, so I initiated an adult chamber music class at Austin Community College. Again, the outcome of that experience I couldn’t have imagined either. Besides being a ton of fun for me, Leslie met three other women in the class who decided after the term was over to get together once a week to play string quartets. Four women, ages spanning four decades, meeting together religiously for the next decade and a half to mine the works of great composers… talk about your outcomes. I recently bumped into Lola (the oldest member of the group who is now in her 70's) and she said the group still meets regularly, braving in weekly installments the vast repertoire of string quartets.

So back to the original question, if I may wax rhetorical. Is it too late to embark on a journey that will stretch you emotionally, mentally, and physically? Is it too late to engage in an art form, an ineffable vehicle for personal expression that does not rely on emails or facebook status updates? Is it too late to learn you have perseverance and determination you never knew you had? I guess the question really is: Why wouldn’t you learn to play the violin as an adult?

But that's the chicken. Here is the egg. Approximately 17 years ago, before there was ever a Violin Lab, I started an adult chamber music class at Austin Community College. I already had a booming private studio of young talented kids, and one beginning adult student, a thirty-something year old, who had played some brass instrument in junior high band, but passionately wanted to learn the violin. Leslie was her name and she was my first adult student.

She came to lessons knowing how to read music, but that was about it. She experienced a lot of anxiety in lessons, her nerves manifesting obvious tremors in each bow stroke. After our first couple of lessons, I thought for sure she wouldn't last. I saw the long, arduous battle in front of her, and many times, I must admit, I thought of suggesting that she choose another instrument, something easier, like piano or guitar. What I absolutely couldn't see then was the depth of her resolve, nor could I have anticipated what she would accomplish over the next several years, reaching a level of proficiency rivaling that of a much younger student. Although she was still subject to nervous anxiety, (it frustrated her to no end) she never let it stop her. She eventually tackled the Mozart G major Concerto, Kreutzer Etudes, and a few Handel and Corelli sonatas. As I watched Leslie develop into a competent violinist, my own ideas and feelings changed about teaching adult students. Perhaps I had bought into what our goal-oriented society tells us: that unless we can “master” or “monetize” something, then why bother doing it? And certainly, given the extreme difficulty of learning the violin, if you missed the boat when you were young, then you were better off doing something easier. We are rarely encouraged to dedicate ourselves to a goal simply to develop our artistic selves, nurture our souls, or expand our ways of thinking, detached from any outcome.

Teaching Leslie opened my mind to the idea that learning to play the violin was about self-discovery through process and opened my heart to feelings of outright jealousy.

Throughout my then 25 years of playing the violin, I had enjoyed many technical milestones and accomplishments. I had experienced the utter poetry of pulling deep resonating tones from ancient wood with a stick that felt like a feather beneath my fingertips. I had performed pieces where in pure sweet moments of transcendence I had merged so deeply with the melody that I lost my sense of self. But because I started as a child I had never experienced what my adult student had: the burning desire to learn the violin; the self-propelling passion that comes from choice, the will to continue because it was what I wanted more than anything. Those things I had never owned. For me learning to play was the byproduct of a childhood activity chosen and nurtured for me by my mother, like an arranged marriage, and later the byproduct of a vocational decision to the dilemma faced by every young adult: “What am I going to be when I grow up?”

After a few years of lessons, Leslie’s skills were sharpening and I thought it would be nice for her to play with other people, so I initiated an adult chamber music class at Austin Community College. Again, the outcome of that experience I couldn’t have imagined either. Besides being a ton of fun for me, Leslie met three other women in the class who decided after the term was over to get together once a week to play string quartets. Four women, ages spanning four decades, meeting together religiously for the next decade and a half to mine the works of great composers… talk about your outcomes. I recently bumped into Lola (the oldest member of the group who is now in her 70's) and she said the group still meets regularly, braving in weekly installments the vast repertoire of string quartets.

So back to the original question, if I may wax rhetorical. Is it too late to embark on a journey that will stretch you emotionally, mentally, and physically? Is it too late to engage in an art form, an ineffable vehicle for personal expression that does not rely on emails or facebook status updates? Is it too late to learn you have perseverance and determination you never knew you had? I guess the question really is: Why wouldn’t you learn to play the violin as an adult?

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Best Practices: Efficient Violin Practice : "Change the Landscape"

When I go to gym class, my gym instructor makes us use different equipment each time. One day it's the Bosu ball, the next it's the stretchy leg band ( they're really not that stretchy!). She says that we'll see a bigger gain by switching things up, that the muscles learn better that way, otherwise they plateau. I think that idea applies to violin practice as well. If we practice the same notes, the same way, using the same part of the bow, same dynamic....(you get the idea)... we can get stuck. Save the small gain of exhaustive repetition, our body and brain stop learning. However, by making contextual changes for a given note passage we can create new experiences for our mind and muscles.

I recently interviewed the incredible violinist and teacher Dan Kobialka at Violin Lab who talked about dimensionality. I loved the word and now have added it to my own lexicon of teaching terms. Dimentional learning is how we broaden our practice experience and thereby see faster gain.

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

Best Practices: Efficient Violin Practice : "Extreme Conditions (part 2)"

One of the ways I push myself to the extreme limits of my ability is to play as fast as I can (or can't). I don't do this often. Back in the ol' college days, I was taught that playing very slowly was the best practice technique there was, and certainly there is no substitute for allowing the brain to absorb loads of information at slow tempi. But there are times when pushing my tempo to the very threshold of manageability serves a purpose. I realize that I have forced something out of myself, begged a particular left hand/right hand communication, and challenged myself to fly out of my comfort zone. And in the end, when I ultimately crash and burn I find that I even had fun.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Best Practices: Efficient Violin Practice : "Extreme Conditions (part 1)"

Have you ever done that experiment where you hold up your arms while someone pushes down on them for while with all their might...then they let go... and your arms fly up, feeling light as a feather. That's the principal behind training under extreme conditions. Athletes do it all the time. And we violinists have been dubbed small motor athletes. I have many times experienced the glorious sensation of ease where the violin seems to play itself after having subjected myself to extreme condition practicing.

Here is the musical example I use for demonstrate. It's the opening of the presto movement from the Bach unaccompanied Partita in G minor:

Friday, May 14, 2010

Best Practices: Efficient Violin Practice : "Zoom In"

We've all seen those movies where forensic scientists are sitting around a computer screen looking at magnified DNA images, then the computer analysis specialist repeatedly hits a key that successively magnifies the already super magnified picture of blood samples.. Ok, so imagine you're one of those scientists, but instead of blood samples it's a magnification a string crossing or a shift. Keep zooming in until there is nowhere left to go. You are focusing on the very muscle movement/s responsible for executing the notes you are wanting to play.

This spot in the Bach C major Sonata always gives me grief.

--Beth Blackerby

creator and founder of ViolinLab.com

Thursday, May 13, 2010

Best Practices: Efficient Violin Practice: "Isolation"

Imagine you're trying to unearth ancient artifacts of a lost civilization thirty feet underground and you're digging in the wrong place. One of the first tenants of practice is isolation: separating the bits that are problematic and putting most of your energy there.

--Beth Blackerby

creator and founder of www.ViolinLab.com

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

My Secret Practice Technique #3

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

My Secret Practice Technique #2

Monday, May 10, 2010

My Secret Practice Technique #1

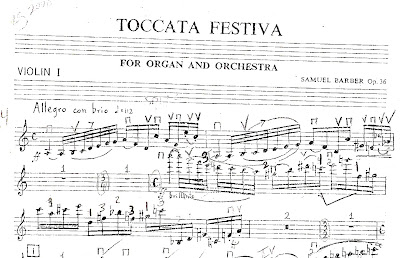

I know I speak for all the orchestral violinists out there when I say how sometimes our spirits sag a little when we pick up our orchestra parts for practice and we see a jumble of ledger lines, fast tempo markings and crazy accidentals. When that happens, I just have to calmly sit myself down and apply these somewhat unorthodox practice methods. Here is an candid demonstration of one of those real life moments.

Below is the musical Rorschach test I'm working on. (I see a butterfly....)

Sunday, May 9, 2010

Violin Playing: How to Practice

I have an aversion to routine. Any task that smacks of repetition soon becomes a chore. That's probably why I haven't achieved any degree of success in the "Domestic Arts". Doing laundry, dishes, traveling the same worn paths to after-school activities often puts me in a funk of existential angst. So how have I become a professional violinist, a vocation that is clearly built on layers of routinely repeating repetitive repetitions?

Honestly, I can't answer that question, but I do know that the hours I spent in a practice room becoming a classical violinist went beyond merely playing notes over and over hoping for a better outcome. My most potent discoveries and epiphanies came when I approached the formidable task of "improving my violin playing" in the way a scientist goes about uncovering hidden truths behind incomprehensible phenomena, or an engineer searches for the most efficient mechanical system.

I no longer think of practicing as practicing (although I still say "I have to practice"), but as discovery. I unleash my powers of analysis and creative problem solving, and believe that there are truths and answers that I have yet to understand. So I dig, compare, try out different mental commands, hoping that I'll find just the right thought or elbow angle to produce the results I'm after.

In my next several video blogs I will share some of my practice methods, old favorites that have helped me and my students get more out of "practice". And I invite any of you readers to share your brilliant observations and discoveries as well.

--Beth Blackerby

founder and creator of www.ViolinLab.com

Honestly, I can't answer that question, but I do know that the hours I spent in a practice room becoming a classical violinist went beyond merely playing notes over and over hoping for a better outcome. My most potent discoveries and epiphanies came when I approached the formidable task of "improving my violin playing" in the way a scientist goes about uncovering hidden truths behind incomprehensible phenomena, or an engineer searches for the most efficient mechanical system.

I no longer think of practicing as practicing (although I still say "I have to practice"), but as discovery. I unleash my powers of analysis and creative problem solving, and believe that there are truths and answers that I have yet to understand. So I dig, compare, try out different mental commands, hoping that I'll find just the right thought or elbow angle to produce the results I'm after.

In my next several video blogs I will share some of my practice methods, old favorites that have helped me and my students get more out of "practice". And I invite any of you readers to share your brilliant observations and discoveries as well.

--Beth Blackerby

founder and creator of www.ViolinLab.com

Saturday, May 8, 2010

Too Much Pachelbel Cannon?

Had Johann Pachelbel known that three centuries later his beautiful Cannon in D was to float millions of brides down the aisle to the marriage alter, he might have planned his estate better. In my career alone I have cycled those heavenly harmonies thousands (maybe just hundreds) of times to the elegant rustling of bridal trains.

The Pachelbel Cannon is a perfect example of "simple is beautiful". A repeating eight-note cello line underpins florid melodic passages, one following the next, like in a round. The intricate interwoven melodic textures over a hypnotic pulsing bass line have made the Pachelbel an eternal favorite.

Here is my quartet playing the top #1 bridal processional. We originally shot this for a promotional video for our quartet website (Barton Strings).

For anyone who would like to count all twenty eight iterations of the cello line ....

The Pachelbel Cannon is a perfect example of "simple is beautiful". A repeating eight-note cello line underpins florid melodic passages, one following the next, like in a round. The intricate interwoven melodic textures over a hypnotic pulsing bass line have made the Pachelbel an eternal favorite.

Here is my quartet playing the top #1 bridal processional. We originally shot this for a promotional video for our quartet website (Barton Strings).

For anyone who would like to count all twenty eight iterations of the cello line ....

Friday, May 7, 2010

"The Lover's Waltz" by Jay Unger

One of the members on ViolinLab.com requested that I play "The Lover's Waltz", a work written by Jay Unger and Molly Mason, the same composers who wrote "The Ashoken Farewell". It is such a lovely piece. I invited a good friend and talented musician to join me for this little presentation. I hope you enjoy it.

Thursday, May 6, 2010

How to Not Sound Like a Sick Cat

The stereotype of a screeching, squawking violin sound would not exist if everyone in the world understood these few simple concepts about: bow direction, bow speed, pressure, and placement.

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

ME, ME, ME

One of the members of www.ViolinLab.com posted a request to "hear my story". It is not at all illustrious. So for the very few who would like to know of my humble violin beginnings, this is for you.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)